IFSI Library Lending Policies

Local Lending (Illinois Residents Only)

- The checkout period is 4 weeks.

- Extensions are considered individually.

- Pick up requested materials at the library circulation desk.

- Bring your photo ID to set up a lending account.

Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- The checkout period is 6 weeks.

- IFSI can send materials directly to your local public library through Interlibrary Loan.

- You must have a public library card.

- It may take up to two weeks for items to arrive.

Cherry Mine Disaster: Introduction

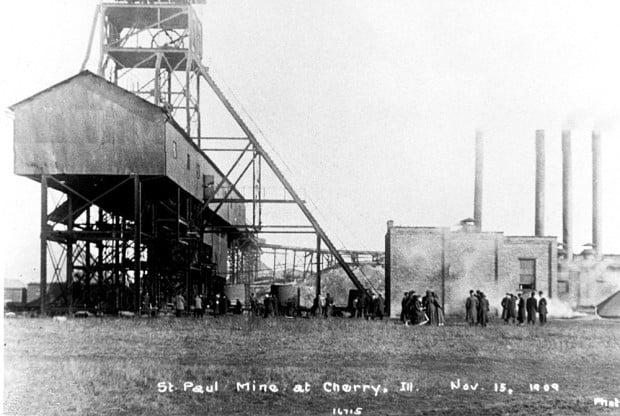

Photo from the Bloomington Pantagraph.

In 1905, the St. Paul Mine Company began mining coal in Cherry, Illinois. Believed to be the largest coal shaft in the United States, the Cherry Mine produced over 1,500 tons of coal a day for its first few years. In addition to being profitable, the mine was also considered to be among the most safe and modern mines, in terms of construction and equipment, operating in the country. To demonstrate their prestige, the St. Paul Mine Company outfitted the entire mine with electric lights and even declared it fireproof.

On Saturday, November 13, 1909, while 480 workers toiled in the mine, a cart carrying hay to feed the sixty or seventy mules that pulled the underground coal cars caught fire. The hay cart had been left too close to a kerosene lamp the workers were using for light after the electricity failed. The fire quickly spread to the support timbers throughout the mine, burning for 45 minutes before any efforts were made to evacuate the workers. While some were able to escape, over 250 miners remained trapped. The immediate civilian rescue efforts that afternoon were successful, as a group of twelve men (including a grocer and a store clerk) descended into the mine six times to rescue miners. The fire was spreading rapidly, however, and the amateur rescuers were killed on the seventh trip down. Shortly thereafter the entire Ladd, Ill., Fire Department arrived but the firefighters were relegated to dumping water down the airshafts when the St. Paul Mine Company officials refused to let them descend into the mine.

Rescue attempts did not begin again until the next day, when Professor R. Y. Williams, a mining engineer with the U.S. Geological Survey, arrived from Urbana where he was stationed at the government rescue operation center at the University of Illinois. Williams brought rescue apparatus with him from the State Mine Experiment and Mine Life Saving Station, including newly developed oxygen helmets and tanks. Over the next week, Williams made numerous trips into the mine while directing the rescue and firefighting efforts. Late on Sunday, November 14, Williams appealed to the state fire service community for fire suppression chemicals, additional hose, and more firefighting apparatus. The following day two special fire engines with over 4,000 feet of hose arrived from Chicago along with dozens of wagons containing fire suppression chemicals. One day later, thousands of more feet of hose arrived from Milwaukee and Chicago, along with Chicago Fire Chief James Horan and eleven handpicked veteran firefighters. By Wednesday the firefighters were pumping 600 gallons of water into the mine per minute, and on Thursday the first firefighters entered the mine.

The rescue efforts culminated on Saturday, November 20, when twenty miners emerged alive, one week after the fire started. Soon after, the St. Paul Mine Company sealed off the mine while the fire continued to burn below the surface. Three months later, the mine was reopened to recover the remains of the lost miners. In the end, 259 miners were dead, leaving 160 widows and 390 children. Public outcry over the disaster and the company’s subsequent abandonment of the families of the victims led Illinois to impose stricter fire and safety regulations on mines and to adopt the state’s first Workmen’s Compensation Act.

Summary written by Adam Groves.

Resources at IFSI Library

-

Cherry Mine Disaster (Cherry, Ill., 1909) Collection

This archival collection includes secondary resources related to the history and study of the Cherry Mine Disaster.

Cherry Mine Disaster (Cherry, Ill., 1909) Collection

This archival collection includes secondary resources related to the history and study of the Cherry Mine Disaster. -

A Deep & Deadly Fire: The Story of the Cherry Mine Fire Disaster by

This article was published in the November 2009 edition of Firehouse magazine, looking at the disaster 100 years later. -

The Cherry Mine Disaster

by

Call Number: TN315 B855 2023Publication Date: 1910 Republished 2023A first-hand account of the fire that blazed through the Cherry, Illinois, coal mine in 1909, claiming the lives of 268 men and boys, yet trapping twenty men who survived eight-days of struggle to remain alive and who were eventually rescued.

The Cherry Mine Disaster

by

Call Number: TN315 B855 2023Publication Date: 1910 Republished 2023A first-hand account of the fire that blazed through the Cherry, Illinois, coal mine in 1909, claiming the lives of 268 men and boys, yet trapping twenty men who survived eight-days of struggle to remain alive and who were eventually rescued. -

Trapped by

Call Number: TN315 .T56 2002ISBN: 9780743421959Publication Date: 2003-09-17A gripping account of the worst coal mine fire in US history--the 1909 Cherry Mine Disaster that claimed the lives of 259 men. "Drawing on diaries, letters, written accounts of survivors and testimony from the coroner's inquest...Tintori's engaging prose keeps readers on the edge" (Publishers Weekly).

Online Resources

-

How Regulation Came to Be: the Cherry Mine Disaster - Part IThis link is to an in-depth blog post series about the events of the mine disaster, as well as how it has impacted codes and regulation. Part II of the series is linked at the bottom of Part I's post.

-

Report on the Cherry Mine DisasterThis link goes to the Illinois Digital Archives, where a copy of the Illinois Bureau of Labor Statistics' report on the disaster is located.

Videos

This is a short documentary detailing the events of the mine disaster.

Librarian

IFSI Library Information

Library Hours:

8:00 am - 5:00 pm

Monday - Friday

Special operating hours may be held during events.

IFSI Library Staff:

Lian Ruan, Head Librarian: lruan@illinois.edu

Diane Richardson, Reference & User Training Librarian: dlrichar@illinois.edu

David Ehrenhart, Assistant Director for Library Operations: ehrenha1@illinois.edu

IFSI Library Facebook:

Libguide created by Quinn Stitt

Contact fsi-library@illinois.edu with questions or concerns.