Kazakh Folk Resources

This Encyclopedia Britannica article offers a brief historical overview of Kazakh culture.

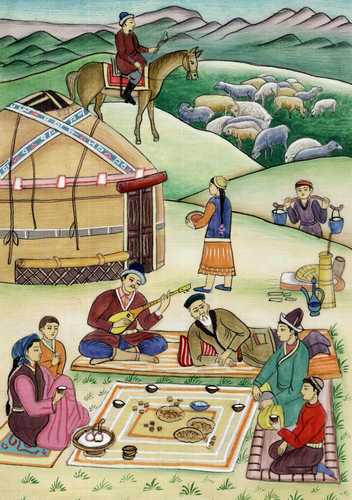

While Bukhara-Carpets is an enterprising website, it does offer an overview of traditional Kazakh jewelry, musical instruments, costumes, and housing.

The national website Visit Kazakhstan offers information on national Kazakh wear, Kazakh traditions, and the traditional Kazakh yurt.

This Library of Congress country study: Kazakstan, Kyrgyzstam, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan: country studies is available in digital format.

Kazakh National Clothes

Kazakh Traditions

Traditional customs in Kazakhstan taken from OrexCA.

Zharys Kasan is a celebration on behalf of a long-expected and desired baby. Children have always been highly prized by the Kazakhs. Kazakhs have always been known as a very generous people. For example, when an unexpected guest came to the house, the host would often butcher the only horse he owned in honor of the visitor. The same practice might be followed if the household was blessed with a child.

Shildekhana

A second celebration of new life in the Kazakh tradition was called the Shildekhana, and this gathering also included the participation of many young people. All participants donned their best clothes and rode their horses to the event if they had one. Others rode their bulls, and sang songs en route to the celebration. Elders came to give a "Bata", or blessing. Invited participants ate, had fun, and sang songs to the tune of the dombra, a traditional two-stringed instrument. Young people playing this instrument were expected to compose and improvise songs during the singing.

During the Shildekhana, the godmother sliced the boiled fat from a sheep's tail and put it in the baby's mouth. In this way it was believed that the baby would learn how to suck. And the baby who was trained in such a manner was believed would never have stomach trouble.

Besik Toi

The arrival of new birth, whether it be of a foal, calf, or baby also involved another celebration called Besik Toi. For babies, the tradition of Besikke Salu was practiced and involved placing the baby in the cradle for the first time. Special foods are prepared, and all the relatives, neighbors, and nearby children are invited. Guests to the feast brought "Shashu," or candies, kurts, and coins. The baby's cradle is made by a special master carver. Only women who have conceived their own children are allowed to place babies in their cradles, and any woman who would place a friend's baby in this place of honor must sew and present a new itkoiiek to the baby's mother.

The symbolism of the cradle is important in Kazakh tradition, which may be one reason that the Kazakhs often call their native place "Golden Cradle." When a mullah would be present for the Besik Toi, he would shout the baby's new name into his ears. And in ancient times, seven items - including a whip, a bridle, a fur coat, and a blanket would be placed in the cradle. Each of these items meant something to the family. A bridle and a whip signified family hopes that the baby might ride a horse, be brave or even become a batyr.

Tusau Kesu

After the baby's cradle and crawling stage, the scene is set for another celebration: when the baby begins to walk for the first time. Wealthier parents would butcher a cow for this celebration; less wealthy parents, a sheep. For the ceremony, black and white thread was prepared in advance to tie the baby's legs. The mother would ask one of the more energetic woman first to bind the baby; and then to cut the string. In this way the baby's first step would be toward his mother. Everybody would then wish the family great success for the baby's future. Here the reader might ask a question: Why use black and white thread instead of red or green? White is symbolized in this case to mean hopes for success without any obstacles. Black and white is associated with the concept of honesty, even to the level of taking a thread which does not belong to you. Cutting of such a thread meant if you see a person stealing something or an unpleasant situation, the watcher should try immediately to intervene.

Sundet toi (Circumcision)

If the baby was a boy, four or five was the age for circumcision and another toi. It was one of the remarkable days of a boy's life. Again relatives and friends of the family gathered, ate, and had fun. All the above mentioned traditions, except Sundet, were celebrated in honor of both son and daughter. From this point on we'll talk about boys and girls upbringing separately, because a son's upbringing was accomplished by the father, and a daughter's by the mother.

Mounting Ashamai

Boys until the age of seven were believed to be too prone to injury for aiding their families. After this age they were increasingly encouraged to imitate their fathers, taking a stick and pretending to ride a horse, and watching how their fathers led the cattle to grazing. An ashamai is a kind of a saddle. It was made of wood according to the boys size. On the front and the back it had support or backing, but it had no stirrup. There was a soft pillow inside. The father put the ashamai on a horse and then placed his son on it. Before that. he would bind his son's two legs in order to protect him from falling,and he bridled the horse. Gradually the boy learned how to ride without his father's help. Almost half of a male kazakhs life was spent on a horse. That is why the ashamai is celebrated as the first attempt to ride a horse. This toi was also marked differently according to the family budget. Wealthier people would slaughter a horse; those who couldn't afford this might butcher a fat goat to make their feast.

Tokym kaqu, bastan

Soon after Ashamai, or near the age of ten, the boy would ride his tai or young horse on his first long trip. His parents would wait for him and arrange Tokim Kagu, which meant "waiting for the boys quick arrival" from the trip. Again, they would invite guests while the father prepared the harness: a saddle, horse collar, harness strap, whip, bridle, stirrup strap, and breastplate all to be fastened to the saddle and saddle girth. Childhood for boys also involved other activities.

Kozy jasy

After ten years of age, a boy would be considered to be on "kozi jas," because at that age his parents would trust him to graze a lamb. It would be the beginning of labor training. Kazakhs from early times were concerned to bring up their children to be industrious. From an early age the boy could help his father to feed and graze cattle. In such way he might become healthy and strong. It is still necessary in the rural places of Kazakhstan to bring up boys to be able to look after the cattle. Urban boys of this age today are unlikely to be able to distinguish from among domestic animals or be familiar with the names of the offspring of different animals. They are only familiar with their multi-storied buildings, and if they came to the village to visit and were asked by their grandmother to chop the wood, they often hurt their legs with the axe. The forefathers advice for Kazak sons only works for rural ways.

Koi jasy

When a boy reached fifteen years old, he was considered to be ready for the Koi Jas, a time when he would be trusted to graze the family sheep without supervision. The Koi Jas period lasted from ages fifteen to twenty five, and during that age he could marry. Camels and cows could usually be tended older family members, but kazakhs usually also had sheep, and horses reguiring more shepherding skills. To successfully perform Koi Jas duties, the teenager had be able to graze a flock of sheep in rainy, windy, or sunny weather, as well as to protect them from wolves and wild dogs. This was a difficult task, but the ultimate task for a young Kazakh male. Those who successfully mastered these sheep tending skills gradually moved into "Zhiiki Jasi".

Zhylky jasy

The age of twenty five symbolized entrance into a period of youth and strength. In early times, zhigiti (or young men) of one clan were sometimes charged to drive off another clan's cattle in the case of an intertribal feud. To protect the livestock, only the strong zhigiti of twenty five to forty years of age were trusted to graze the important animals. It was also their duty to graze the animals in periods of windy winter weather, when starving packs of wolves were also likely to attack sheep as well as horses.

Patsha jasy

There were no tsars among the kazakhs but you've heard that there were khans who were the equal of tsars. According muslim law, even if a person was wise and clever enough to be monarch or tsar this could not be allowed if a man wasn't yet forty. For kazakhs this age, Patsha Jasi, was likened to the development of a sharp sword; it took this long to be polished or to become respectable and clever enough to become a khan, sultan, or the holder of some other honorable position like a poet or hero.

Satyp alu (to buy)

In many Kazakh families children died young. There were two remedies for couples who had lost young children previously: either to buy a child or to adopt one. For buying purposes, an old woman was required. She is instructed to follow and observe the child of parents concerned for the well-being of a young child, and must only come to the parents home at night. She shouts loudly: "I found the thieves, I know who has stolen my baby. Give me back my child." The old woman wears a torn dress, and looks like a witch. In her hands she carries a stick with an eagle's and owl's claws. The couple feigns to be scared of the old woman, and puts the "sick" baby into her hands. The old woman then takes the baby to her home, but the mother continues to nurse the baby at different times during the day. When several months have passed, the parents of the "stolen" baby begin to wear old cloths and to appear as beggars. They then take their kettle, a harp of wood and three or four sheep to the old woman's house to try to buy their baby back. The old woman would meet them at the door and give them a flat cake. The "beggars" would refuse to take it, and ask to buy their baby back. In the Koran, the scriptures implore everyone to pity beggars; to be kind to them and not refuse genuine requests. This is why the couple has come to the old woman in rags, for the old woman cannot refuse their request. She returns the baby head-first, for when a baby is delivered from his/her mother's uterus, the head also appeared first. Kazakhs believed that a human born head-first would die standing, which was highly valued. The old woman gave the baby head first, meaning she hoped he would live a long life. Meanwhile, the baby's parents would leave everything they brought: sheep, kettle and a harp of wood. If the "bought" baby also dies, the next time parents might give him or her to their relatives to adopt. Both of these strategies were thought might protect children from death.

Kudu tusu, biz shanshar (Matchmaking)

When a son is considered a grownup, his parents seek a bride for him. They choose a potential match for their daughter whose family is of the same financial position as theirs. Lets assume one family has a son and they have friends with an eligible daughter. They know each other very well, and until the end of their lives would like to stay friends. For that purpose they say "we'll marry our children." The tradition of Kuda Tusu has its own peculiarities. You know that Kazakhs are very generous people, and their houses are always open to guests. In earlier times, a person on a long journey could drop by any kazakh aul, and the host would greet and feed him. After having a rest, the visitor would thank the host and ride on his way. When matchmakers came to visit, they would also stay for the night. These matchmakers, typically old man, would attach an awl (biz shanshar) sometime during his visit, and he would take their host's whetstone. After his departure, the host began'to look for his whetstone, but he would not find it. Instead, he would find an awl attached to a rug. This meant that his previous guest wanted to become related through the marriage of their son. If the intended bride's parents did not ask about their whetstone, the old man would return and speak more directly about his family's intentions. Why did they attach an awl to a rug? It meant that they had a groom and he might be the son of the intended bride's parents. The reason of their taking a whetstone is they wanted to be a matchmaker or "Kudanda". A Kudanda is an oath in front of god. Here "Kuda" means god, "anda" means oath in arable. This was the beginning step of matchmaking.

(Giving) "Oltiri"

"Oltiri" is a compound word with two different meanings: "Oli"- dead," "tiri"- alife. Matchmakers take an oath in front of ancestors, dead and alive. The groom's parents would send relatives to the bride's house with many presents, including a sheep. This sheep is not butchered in the future bride's house, but at the house of a witness to engagement. After "Oltiri," both sides were considered to be matchmakers to the future wedding. The groom's parents would send delicious foods to the future bride's house, but she could not eat them while she resided in her own house. On the other hand, before she would be a daughter-in law she had many conditions to fulfill.

The groom's side would also bring a horse or a cow, as well as an owl's feather, which would symbolize that the daughter of this house would be theirs. For this they would pay "Kalin Mal" - or, flocks of horses. Of course, only wealthy men could give kalin mal to the bride's parents.

Esik koru (Visiting)

After "oltiri" toi has been celebrated, and kalin mal was paid, the groom was allowed to visit his bride's house. If "Kalin mal" was only partly paid, only his parents and relatives could visit. Guests from the bride's family were treated especially well before the wedding. They would be presented good gifts. The groom's first visit to his future announced bride was called "Esik koru". It was celebrated as the time in which two young people met each other for the first time. Sometimes it might happen that they didn't like each other, and the match would be broken. In successful matches, the groom would come with friends who could sing songs, play and improvise on the dombra. There would also be a musical competition at the bride's house. It was also necessary for the groom to come at night, for coming earlier in the day would suggest he had been brought up poorly. Upon his evening arrival, the bride's brothers would meet him and take his horse, forcing the groom to walk. This symbolized that in order to see his bride he would have to endure many obstacles and difficulties. One legend has it that two young people, Leili and Majnnun, were in love without having seen each other.

The sister-in-law of a bride might meet the groom and ask for "Entikpe," which meant they were tired of waiting for him. The groom was also expected to bring expensive gifts for his mother-in-law and father-in law to be. Sisters of the bride would ask him "Korindik," which meant a special gift for showing the bride to the groom. In brief then, "Esuk Koru" meant to see the bride for the first time and to have permission for doing so at the bride's house. For this occasion the parents of the bride would arrange a toi. The groom may stay at bride's house for two or three days, not more. The bride's family would try to please him; filling his bags with gifts to return to his parents and relatives. They then would set the wedding date, and the bride would begin to visit her relatives to say farewell.

Kyz tanysu

The bride would take one of her sister"s-in law or any relative and visit relatives who lived in remote places. When she came to their houses they would present her with something for her dowry: a rug, a blanket, or a dish. Her journey would last between one and two months! Each of her relatives would show her respect, and try to be kind. Some further words about the dowry: the bride's mother would invite women who were skilled with their needle to also contribute. They would embroider blankets, pillows, a table cloth and other necessary things for the home. Before starting this important work however, they ate and had fun. The bride's mother would buy her daughter new cloths and hang them in one of the corners of the yurt. After that, the groom would come. He could talk to his bride but only through her sister-in law, because she was responsible for her care. On this occasion the bride's parents would place him in separate yurt where the young people had fun, joked, played the dombra, and had food.

Kyz Uzatu (Marriage)

Seven or more people from the groom's side would come one day to take the bride back to their house. Whatever the number, it had to be odd. Godparents came first, then the groom would come with his friends. Below we try to describe the "Kyz Uzatu" ceremony.

1. Kopshik kystyrar - This was a gift for the bride's sister-in law for having accompanied the groom. It might be something substantial .. for example, a cloth or fabric for a dress.

2. "Shashu" - was mentioned earlier. When the groom came to the bride's house, one of the respected woman of the aul would throw shashu or special treats. Everyone would try to catch one, for this would indicate a successful marriage for their daughter too.

3. Kyim ilu - This was the name for another gift giving. When those responsible for the matchmaking entered the house, a woman would greet them and hang up their coat. When they left, she would return the coats, upon which she would be presented a special gift for her service.

4. Tabaldyryk kadesi - Here the matchmakers again are expected to give a gift to enter the room.

5. Sybaqa asu - When the matchmakers have taken their places, the hostess prepares a special meat from the previous winter's slaughtering. She puts into the Kazan good parts of meat and pelvic, marrow, and breast bones.

6. Malga bata jasatu - After the sybaga has been consumed and tea is drunk, the host grabs the sheep which was brought to be slaughtered for the celebration, and one of the old men would give bata (a blessing). The slaughter was to occur just before the matchmakers were going to take the bride from her home and to the home of the groom. After the meal, the groom's family side would put money into the dish which earlier contained the meat consumed in the meal. The women from the bride's side would then share it with each other.

7. Kuiryk bauyr asatu - Before starting to eat the meat of the specially slaughtered sheep, the host would make kuirik bauir -which meant boiled and sliced fat tail and liver with sour cream. He would then put slices of the dish into his kinsmen" mouth; the rest of that they would spread on their cloths. After that the matchmaker again would give money to the woman who treated him to kuirik baur.

8. Saga togytu - Following the kuirik baur ceremony, one of the woman would say: Look here! How can our matchmakers appear in public with greasy clothes? Come together kinswomen, let's wash them." This ceremony would usually take place near the river in the summertime. So matchmakers would be pushed into water. Of course, they wouldn't like to be in the water alone, so they would often attempt to hold onto one of the beautiful ladies from the opposite family. If there was no river, wealthy people would sometimes make a special pond for the occasion. I remember it happened when we were children. Bala Kamsa from the wealthy tribe of Kazibek (later he lived in Turkey and died there) made a special lake when he married his son to a very beautiful and clever woman. There were lots of Kamza in those times. Every ritual meant something. You could ask a question such as "Why did they put "kuirik baur" into their mouth?" One possible answer was that "If you'd eat more liver you'd be more friendly with you brothers and sisters." There were two reasons for stirring kuirik baur with sour cream. The first meaning: Kazakhs liked white color, it was associated with sincerity. Second, it would be more tasty. After the matchmakers had been dunked in the river, the host and hostess would present them with new cloths. They would say: "If something was wrong before, this is washed up now. So, this is our present to you; let's have a long term, close relationship."

9. Kuim tigu - According to Kazakh tradition, the matchmakers mustn't sleep. They had to eat, to sing songs, and to tell funny stories the whole night, otherwise the opposite side would sew up their cloths.

10. Bosaga attar - After eating Kuirik baur, the groom is invited to the master yurt. Entering of the yurt is called bosaga attar .

The bride's parents would call the groom and kiss him. There they stayed only a short time. They would especially slaughter a sheep for his sake, and treat him to marrow and breast bones. Asikti zhilik is a special bone for the groom, because it has asyk. Asyk is a national toy of Kazakh boys. Playing with this toy, they learn how to count which would later be important for a herdsman. The groom is treated to that bone in the hope that he might also have a son who would play the asyk. The breastbone symbolized the parent's wish of friendship and to bear together all the good and bad aspects of life.

11. Neke oku - This is also an important ceremony in the life of the bride and groom. If they had shared a bed before marriage, it was considered a sin. Muslims called it "Nimakhram." In Kazakh tradition the marriage ceremony itself is celebrated by a mullah. Lots of people would gather in the room. They were witnesses, and had to taste the wedding water. There they found salt, sugar and the wedding ring. The water would symbolize faithfulness. Sugar symbolized their sweet love for each other, and the ring was to recall memories of the wedding.

12. Kvz kashar-tundik ashar - Here the sister-in law makes a bed for the newlyweds, and it would be placed inside the screen. Then she would close the front felt of the door (tundik). Then she would give the bride's arm to the groom; and for that service he had to give her a present. The bride's tender arm would make it difficult for the groom to breath. After the sister-in-law gave the happy couple a blanket, she received another present and pretend to leave them alone; but hiding somewhere she would intercept or overhear, and in the morning she would understand even more from the groom's face and mood.

13. Shatyr baiqazy - After the wedding the bride would be invited to the marquee, or home of the groom's parents. They would then be told: "you are now married, and can freely without any shyness walk as husband and wife. You'll have your own shanirak-yurt. This time somebody from the groom's family would give a present for shatir baigazi. 14. Korjyn soqu - The matchmakers usually brought a "korjyn," or saddle bag with two compartments filled with presents and sewed closed. Women friends of the bride's mother would then gather to open the korjyn, removing the special presents for the parent's of the bride, these might include a fur coat or other fine apparel and food. All the women, including the bride, would then gather around and taste food items from the korjyn.

15. Moiyn tastau - This ceremony would be held if the bride's family had a separate yurt for young people. A sheep would also be slaughtered, and on this occasion the spinal column would be given to the groom to nibble on. If he nibbled that bone cleanly, it meant that he would please his wife and she would be beautiful for along time. If his nibbling was not clean, he would pay a fine to the sister-in law. This ceremony was intended to teach the young people to be neat.

16. Shanyrak koteru - If you remember, a shanyrak is a wooden circle forming the smoke opening of a yurt. Only men who had children were allowed to lift it. If the ground was flat and the yurt was large, he lifted it with the help of a horse or a camel.

17. At bailar - After the yurt was ready, one of the relatives of the groom would tether a horse nearby. This meant that he wished the young couple to be hospitable and generous.

18. Saukele kigizy - For this event the matchmakers would be invited to the new yurt. The bride's mother would put a saukele on her daughter. A saukele was an old fashioned embroidered headdress for a bride. Upon seeing the saukele for the first time, the mother-in law would give her kinswoman a present called "korimdik." In this saukele the bride looked like a princess; and the entire wedding suit is beautiful.

19. Bosagaqa ilu - After the feast at the bride's yurt, the groom came to reclaim his wife. Before that he would hang a Shapan (oriental robe) at his in-Iaw's threshold. It meant that he was a son, too, of the bride's parents. He would help and protect them. Why did he hang his robe at the threshold? This was a sign that he could be called upon by his wife's parents to work for their household upon their beckoning.

20. Saryn (auzhar) is a kind of farewell or parting. When the bride's side gathered to say farewell to her, women stayed inside and men outside. The bride would weep, for it was of course difficult for her to leave her parents, brothers and sisters. The bride's mother would tell how her daughter would be able to do all the housework and be able to handle a heavy and blackened cauldron. Zhigiti, whom she joked about before the marriage, would say she (the bride) was as small as a button, as thin as a needle and too young to marry. Farewell songs were also sung to the bride who was merely bought by a wealthy person and taken away. The sister-in law who was a friend, would advise her how to behave in a new place, and they would wish her health. If the bride was a beloved daughter, the father wouldn't show his tears. He would ride away and weep somewhere else. The respected bride would be watched far into the distance, and the mother would weep long hours. She of course didn't want to part with her daughter, but there was nothing to be done. Kazakhs believe that daughters were born for another family.

Tosek toi

Kazakhs used to say that it took forty families to raise a daughter to the age of twelve or thirteen; or they would say it was easier to keep a bear than to bring up a daughter. If the daughter remained a virgin until her wedding night, the husband's parents would be happy and would respect and love her. If she was a "woman" already, they would say that she was poorly bred, and they would scold and abuse her parents for that.

The husband's parents expected future generations of their family to be made possible with the marriage of their son. The young wife was expected to give birth within the first year of her wedding. After five and six months of her being in the husbands house, neighboring women began to gossip if the kelin was pregnant or not. Her mother-in law wouldn't ask her directly about her pregnancy; she would know about that through her eldest daughters-in law. Neighboring women also looked for signs of change: whether the young bride was putting on weight or had developed black spots on her face. Kazakhs would look with disfavor upon the bride who failed to become pregnant for several years, for they liked children. Many children were thought necessary for family happiness.

If and when the daughter-in law noticed some changes in her body and face possible due to pregnancy, she would tell it to her sister-in law. The sister-in law in her turn would tell it to her mother, and then the happy mother-in law would invite some women and make a little feast. Men were not invited to this celebration, called "Tosek toi". One of the husbands relatives would hurry to tell this good news to their kinswomen and would get shuinshi (present). Of course, she would be happy to hear about the signs and would give the daughter-in-law anything she wanted. The husband, upon becoming aware of the pregnancy, would then offer his respect and thanks to his wife's parents for bringing up such a faithful and obedient wife for him.

Kelin Tusiru

Following her wedding the bride needed to dismount from her horse a distance from her groom's house and walk the rest of the way. She would be wearing a big white shawl with fringes, and would be accompanied by many young girls. One of the groom's brothers would hurry to ask shuinshi, telling them the bride was coming. When the bride arrived, some women would through shuinshi. As we above mentioned wealthy people would prepare separate yurts for the young. The bride would be wearing a veil, as she was not allowed to show her face until Bet ashar, and she was not allowed to look straight to anyone. If she sat the wrong way the women would gossip, for she was required to be a bit childish and shy.

Bet Ashar, otka mai salu

Betashar, or removing the bride's veil, was an important ritual. A specially invited poet was in attendance; someone familiar with the bride's father-in law, mother-in law, and all the groom's relatives. At the Betashar toi, he would be required to mention details of their character, position, and peculiarities. As each participant was mentioned in the poet's song, the bride was required to bend and greet by making salem. There were slightly different versions of Betashar, but its main purpose was to allow everyone to see the bride. In one version, the poet would take his dombra and sing:

Hear, people, now I take off the bride's veil

I wish you happiness, dear bride,

if you show bad temper, your sisters-in-law would pursue you.

So be patient and not petulant

Your dastarkhan (table cloth) must be spread to any person

who enters your yurt.

If aksakal, the oldest man visits you,

pour warm water.

Be polite and tolerant with your neighbor

don't be idle, try to be clever in your needle work,

Respect your father and mother-in law.

You're so beautiful and white as an egg

don't be lazy, get up early and feed your husband

When elders come to your house, you should rise

be simple and kind,

Do not gossip with the women.

Now people, have a look at her and give me my korindik. Grandfathers bless her, she entered the yurt with her right feet; she'll bring happiness to this house. Believe me ! She was blessed by her folks Now dear bride, come here, Look how many people want to see you through away your veil; greet and bow to this crowd. As we mentioned above, the bride was required to bow when she heard each name of her future husband's relatives. Poets all sang the Betashar on their own way, but the meaning of all of them was similar. The bride was instructed to be polite, loving, kind, generous, industrious, and to respect people. After Betashar, the bride would step over and bow to the shanrak. Then she would sit in a screen. Before stepping over the yurt threshold, the mother-in law would throw some fat into the fire at the center of the yurt. This tradition remained from ancient times, and is still practiced today. Throwing fat into the fire on this occasion was to remind the new bride that as a hostess running her own household that she must remember to always be prepared to receive guests. Throwing fat on the fire made it burn hotter; reminding her that she must always be generous with visitors.

Bie kysyramas

After otka mai salu. the mother-in law would ask the now veil-less bride to sit on her right side. Then the mother-in law would give white cloth to the women in the yurt. They would then begin to bind saba - large leather bags for processing and storing kumiss. Kazakhs' favorite animals were horses, and their favorite beverage was kumiss - a beverage made from mare's milk. So every kazakh family would desire and optimistically prepare to have lots of productive horses in order to make more kumiss. Kazakhs usually had great feasts during the summer in their highland pastures. At this time the horses and cattle would be fat, and the saba always full. They would also process cottage cheese, butter and kurt. The hope was that the female horses would not be dry. All horse products meat, kazy, karta and the national wine kumiss were important for the Kazakh family. In addition, the giving of white cloth to all women in the yurt was symbolic of the respect and love her daughter-in law would enjoy in her husband's household; similar to that of the mother-in-law's own daughter. Kazakhs would say "Kelinnin ayaginan, koishinin tayaginan," which meant, if a good bride entered the yurl everything would be OK in the family's future.

Asykty zhilik, tos (the breast bone)

The bride's family would specially slaughter a cattle for the bride. In the earlier chapters we talked about bones like the asykti zhilik. On this occasion the sister-in law would cut the meat and would give the marrow bone and the peak of the breast bone to the bride. All other women present would also be given something to eat. Should the sister-in-law forget to give meat or a bone to anyone in attendance, such a woman would be offended and assume that her presence in the bride's company was not desired.

That's why it is important for kazakh woman to be friendly and share everything. They would say "Abysm tatu bolsa as kop degen" which meant if daughter's- in law were very friendly with each other, then there would be lots of meals.

Otka shakyru

After the feast organized in the bride's home, the groom's relatives and neighbors would invite her to their yurt. Taking presents with her, this ceremony was designed to introduce the young woman to her new kinswomen in their home; and it was an occasion to once again display the bride's good breeding, for her appearance, beauty and behavior during Otka Shakyru would be the subject of much discussion upon her departure. Elders especially would note whether she was neat or sloppy, industrious or lazy, etc. If they like her, they would say "how lucky that zhigit is to have such a beautiful wife. Look at her eyes! How large they are! How they sparkle! If she was not so beautiful, they would say so. Kazakhs would also say, "before choosing a bride, first see and know her mother." This meant that if the mother was beautiful and industrious, the daughter would be too.

Onir salu

The next ritual following Otka Shakiru was Onir Salu. Here only senior wives gathered; their purpose being to congratulate the mother-in law for her son's new bride. They would bring with them Onir - a present. It might be a cloth, table cloth, a mirror, bands, dishes, or it be an eagle's claw or an owl's feather. Those things would all be necessary for the future hostess. The bride's mother-in law would then treat her guests to food, and she would also give them something from the bride's korjyn.

Kelin Tarbiesi

Kazakhs would never beat a daughter. If the father was not satisfied with her behavior, he would ask his wife to talk with her. Each mother would teach her daughter how to sew, cook dinner, treat guests, and how to please her husband and to mingle with people. Nowadays some of our girls need training in school to replace what they no longer learn from their mothers. Our foremothers could weave, shade, process kumiss, and embroider fantastically. These works required patience and precise skills. After the kelin (or bride) came to the groom's house, her mother-in law and sister-in law would begin to teach her further household works. In early times, only a sister-in law was thought by the new bride to be trustworthy and one to share secrets with her. Even if her parents refused a daughter's request to marry her zhigit, his sister might be called upon to help her escape with the man who had stolen her heart. Here we'd like to tell how the Uighur women taught their daughters to please their future husbands. Let's assume a husband went for a long trip. He might arrive home in either a good or bad mood. His wife was taught to meet him with her charming smile, and to-prepare his favorite dish. She would do her best to cheer him up, and talk soothingly to him to calm him down. Uighur women were rumored to be very experienced in terms of love-making, while Kazakh women were thought to be more modest. A Kazakh girls upbringing might not involve secrets of the bridal chamber, but it did include instruction on how to address, respect, and not contradict her future husband. After moving into her husband's house she would also have learned never to call her father-in law or brother-in law by their real names. Instead she would have to invent a nickname suitable for each.