About the Exhibit

'You Can’t Move Mountains By Whispering at Them!': Women Performing Music

Curated by Kathleen McGowan

Ideas and narratives about “women in music” often tell us as much about the times and thinking of the people retailing them as they do about the women making music. The best of these narratives depict women metaphorically moving mountains in the form of systemic biases, gatekeeping, and received historical wisdom about what it means for women to make music. Often it’s the narratives and standards around them that create obstacles and not the art-making itself. The title of the exhibit is a reference to an interview with P!nk about her music video for “F**in’ Perfect” and her advocacy for youth mental health; it seems to be the code that she and many other women musicians have had to live by, especially when they were trying to make music in a world that did not have preordained roles for them.

This exhibit examines some of the ways women in the Western world have performed music at different moments in history, and how they have contended with the restrictions that their societies placed on them. Examining their work this way creates opportunities to see and hear where boundaries break down—many of these women are/were composers, performers, copyists, editors, publicists, and impresarios for their own work long before the “portfolio career” had a name. They also have each had to contend with the gendered expectations of their times and places, and if/how they would conform to them (or not!).

Revolutionary Women in Music Playlist

This playlist was curated by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to accompany their Revolutionary Women in Music exhibit.

Library Materials on Display

-

The Arts of the Prima Donna in the Long Nineteenth Century by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML1705 .A787 2012 -

Babylon Girls: black women performers and the shaping of the modern by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - PN2286 B76B3 -

Bands of Sisters: U.S. women's military bands during World War II by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML1311.5 .S85B3 2011 and Online -

Black Women in American Bands and Orchestras by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library Reference Non-circulating - ML82 H36B5 -

Eden Built by Eves : the culture of women's music festivals by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML35 M67E3 -

Female Composers, Conductors, Performers: Musiciennes of Interwar France, 1919-1939 by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML82 .H355 2018 and Online -

Girl Power: the nineties revolution in music by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML82 .M456 2010 -

One Woman in a Hundred: Edna Phillips and the Philadelphia Orchestra by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML419.P486 W45O5 2013 and Online -

Performing Self, Performing Gender: reading the lives of women performers in colonial India

by

Call Number: Main Stacks - PN1590.W64 B42 2017

Performing Self, Performing Gender: reading the lives of women performers in colonial India

by

Call Number: Main Stacks - PN1590.W64 B42 2017 -

Queer Country by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML3524 .G64 2022 and Online -

Raising the curtain : recasting women performers in India

by

Call Number: Main Stacks - PN2881.5 .S56 2017

Raising the curtain : recasting women performers in India

by

Call Number: Main Stacks - PN2881.5 .S56 2017 -

Revenge of the She-Punks: a feminist music history from Poly Styrene to Pussy Riot by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML82 .G64 2019 and Online -

Sounding Out: Pauline Oliveros and Lesbian Musicality by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML410.O5834 M63S6 and Online -

Wendy Carlos's Switched-On Bach by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML410.C26496 K4 2019 and Online -

Women and Music in the Age of Austen by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML82 .W633 2024 -

Women Icons of Popular Music by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML82 .H39W6 2009ISBN: 9780313340833

-

Anthology of text scores byCall Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - ML410.O5834 A584 2013

-

Les pièces de clavessin : premier livre byCall Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - M24 J333P5

-

Nineteenth century English art songs.Call Number: Music and Performing Arts Library - M1619 .N564

-

Selected Songs byCall Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - M1620 L36S4

-

Sun Warrior byCall Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - F. M1045 .A43S8 2023

-

This love between us : for baroque orchestra, choir, sitar and tabla (2016) byCall Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - M2000 .E86T4 2017

-

The Ursula antiphons byCall Number: Music & Performing Arts Library

-

Working women's music : the songs and struggles of women in the cotton mills, textile plants, and needle trades, complete with music for singing and playing byCall Number: Oak Street Library (Request Online) - M1977.W64 W67

-

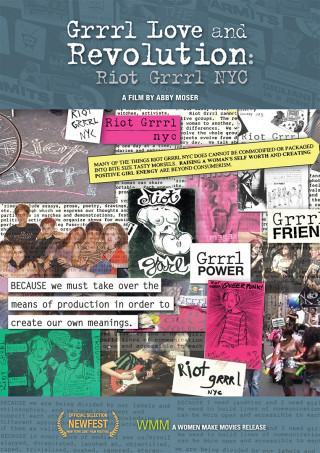

Grrrl love and revolution : Riot Grrrl NYC

by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - DVD ML421.B23G77 2011

Grrrl love and revolution : Riot Grrrl NYC

by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - DVD ML421.B23G77 2011 -

Lesbian American composers.

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - CDISC M1 L47 and Online

Lesbian American composers.

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - CDISC M1 L47 and Online -

Meredith Monk byCall Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - DVD GV1785.M66 M4741996

-

Music for the Mass by nun composers.

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - DISC M2010L46 P7OP.18

Music for the Mass by nun composers.

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - DISC M2010L46 P7OP.18 -

Photography : orchestral works

by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - CDISC M3.1 .W236P4 2016

Photography : orchestral works

by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - CDISC M3.1 .W236P4 2016 -

Pièces de clavecin (1687)

by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - CDISC M24 J22P4

Pièces de clavecin (1687)

by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - CDISC M24 J22P4 -

Sonic seasonings

by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - DISC M1473 C37S62

Sonic seasonings

by

Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - DISC M1473 C37S62 -

Switched-on Bach 2000

by

Call Number: Music & Performing arts Library - CDISC M3.1 .B224S9 1992

Switched-on Bach 2000

by

Call Number: Music & Performing arts Library - CDISC M3.1 .B224S9 1992 -

Women composers : the lost tradition found.Call Number: Music & Performing Arts Library - CDISC M1 W664

Exhibit Photographs

Women & Music in the Age of Austen

Linda Zionkowski & Miriam F. Hart, eds.

Bucknell University Press, 2024

Women & Music in the Age of Austen is an interdisciplinary collection of essays from the fields of musicology, literary studies, and gender studies. The collection challenges common binaries in the discourse of women and music in Austen’s time, including: professional vs. amateur musicians, differences between public and private music-making, and the status of composers and performers of music. It also blurs the usual boundaries surrounding gender roles, class, and nationality. This kind of collection is becoming more common in music studies as performers and scholars conduct research and advocate for representation of historically overlooked music figure and roles.

Check out the essay “‘That ecstatic delight’: Gender and Performance in Adaptations of Sense and Sensibility” by Dr. Gayle Magee (UIUC School of Music).

Working Women’s Music

Evelyn Alloy; Martha Rogers, music notation

New England Free Press, 1976

Alloy’s volume compiles a selection of tunes collected from women working in the United States in textile and garment trades. At the time Alloy was writing her book, the women who sang these songs were part of an aging population that had very different jobs from women the 1970s. She wanted to preserve both the music that these women made and some of the cultural context surrounding it.

The Arts of the Prima Donna in the Long 19th Century

Rachel Cowgill and Hilary Poriss, eds.

Oxford University Press, 2012

This edited collection investigates the lives, careers, and performances of female opera singers in what is often called the long 19th century (1789–1914). Female characters and the women singers who portrayed them became much more prominent in 19th century opera, and many of them still define opera as a genre. The prima donna was not only the “first lady” of the opera while onstage—she influenced how composers wrote leading female roles, how other artists interpreted them, and management decisions about how opera houses were run, what appeared in the operatic season, and which other musicians were employed with them.

Women Composers in Religious Communities

Life in a religious order was historically often a refuge for women intellectuals. It offered them opportunities to pursue scholarly and artistic work in ways that secular life did not, and they got to do so in all-women communities.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) and Isabella Leonarda (1620 –1704) are two representatives of the many musicians in Western Europe who were also nuns. Hildegard of Bingen looms large in studies of medieval music because much of her chant has survived—no mean feat for medieval manuscripts. Leonarda served as music instructor at the Collegio di Sant’Orsola (College of St. Ursula), an Ursuline convent in Novara, Italy. Eventually she was named Mother Superior.

St. Ursula is the patron saint of the Ursuline Order of nuns, Catholic education, students, teachers, and the Univ. of Paris. The Order founded schools for the education of women and girls throughout Europe. She is a common subject and dedicatee of music by women religious composers.

Creative Control

Composers/Performers/Impresarios

In the 21st century many women choose to make their careers as composer-performers who perform and promote their own music, some exclusively and others in addition to performances by other ensembles. In earlier years many women not only performed their own works but did much of the work typically outsourced to editors or promoters—sometimes to save money, sometimes because it was the only way the work would get done and the music would be performed. Two composers appearing here, Errolyn Wallen and Meredith Monk, are performing their own work. Wallen sings on the recording of Photography and Monk sings/plays/dances/choreographs in the

excerpts of her performance Facing North. Reena Esmail’s work (center case, below) reflects the influence of performing Indian classical music on her composition style.

Festivals have also given many women performers opportunities to establish themselves or explore creative outlets in ways that concert hall performances might not allow.

Performing Song Repertoire

“Oh! certainly,” cried [Miss Bingley], “no woman can really be esteemed accomplished who does not greatly surpass knowledge of music, singing, drawing, dancing, and the modern languages, to deserve the word!”

– Jane Austen, Pride & Prejudice

Before recording technology was developed and became widely available, the primary way to hear music performed was at a concert or if a family member played at home. In the 18th and 19th centuries music was considered an “accomplishment” that was both appropriate and desirable for well-off women who wanted to marry well. As Ruth Solie has discussed at length in her essay “Girling at the Parlor Piano,” performing music in domestic settings, particularly on a piano, became an important social means of enforcing gender roles and performing femininity and respectability. Art songs such as those included in the scores in this case were popular repertoire for women performing at home; they were also considered sufficiently feminine for women composers, by the standards of the day. Similarly to visual art, the forms considered “appropriate” for women were small/short and usually carried associations with domesticity.

Sonic Seasonings (Wendy Carlos, Columbia 1972)

Sonic Seasonings is a studio double album by Wendy Carlos, originally released by Columbia Records in 1972. The CD recording was remastered and released in 1988. Carlos was a keyboardist and composer who originally studied physics before she specialized in composing electronic music at Columbia University. In the late 1960s Carlos was known for her adaptations of music by Bach for the Moog synthesizer. Her first album, Switched on Bach, is credited with bringing synthesizers into popular music—they had previously been considered experimental.

Sonic Seasonings features music based on the four seasons and combines field recordings with sounds from a Moog synthesizer. The LP in this exhibit reflects an important aspect of Carlos’s life—her social identity changed after this album went to press, and it reflects her previous name. We’ve chosen to include it to give the artist due credit for her pioneering work. Subsequent pressings and rereleases of her recordings typically reflect her chosen name, as does our library catalog.

Anthology of Text Scores (Pauline Oliveros, 2013)

Pauline Oliveros was a major figure in the development of electronic and experimental music. Her early work in the 1960s with the San Francisco Tape Music Centre led her to develop the Expanded Instrument System—a unique system of tape loops, delays, and reverbs for live effects processing. Her philosophy of Deep Listening began in a 1988 performance in an underground cistern, and has had genre-altering influence on avant-garde classical music since. The anthology contains over 100 pieces that span four decades of Oliveros’s creative work.

Like Wendy Carlos and other composer-performers in this exhibit, Oliveros pioneered technologies and methods that reflected the music she wanted to make instead of the music that was acceptable to her contemporaries. She and Carlos both challenged the association between technology and masculinity in the 60s, and lives to see their influences on electronic music become standard industry practices.

Sources in Popular Music

The prevalence of media, primary sources, and recordings in popular music have made for rich conversations about women performers and their roles in it. Written and recorded interviews, in particular, have made it possible to speak to these women as well as about them in ways that are often impossible for historical figures.

Women in Large Ensembles: Advocacy

A continuing area of advocacy for women performers is representation in large institutional ensembles, such as orchestras and wind ensembles. Baltimore Symphony oboist and activist Katherine Needleman is one of many musicians currently calling for change in the attitudes and hiring practices of these ensembles.

Chard Festival of Women in Music

The Chard Festival of Women in Music was six-day festival held annually in Britain from 1990–2003. The goals of the festival were to commission new music, support ensembles, and promote women composers. Alberga’s Sun Warrior (1990) is one of their commissions, and premiered in Somerset with the Chard Festival Women’s Orchestra directed by Odaline de la Martinez.

Composer’s note: “The ‘Warrior’ represents the soul seeking enlightenment. In three movements, the piece reflects the journey of the warrior-soul. ‘Red Dawn’, the first movement, heralds the beginning of spiritual awakening. The second movement, ‘Mirrors of Blue’, suggests the state of meditation or reflection, a peaceful transition to boundless dimensions. ‘Golden Palace’ portrays the joy of attaining wisdom and enlightenment. (https://www.eleanoralberga.com/)

Instrumentation: 1.1.1.1/2.0.0.0/timp/str

Elite women

Mirroring histories of music more broadly, histories of women in music tend to have a bias toward elite, prominent, or wealthy women. These women often had resources at their disposal—including time, money, materials, education, flexibility with social expectations, and servants or other means of outsourcing work—that made doing and preserving their work in music easier.

Élizabeth-Claude Jacquet de la Guerre is one such figure. She was a child prodigy born into a musical family in Paris; her father taught her earliest lessons, and she first performed for the French court at Versailles when she was five. She eventually became a court musician and received generous patronage for most of her life, including for the Pièces de Clavecin (facsimile, this case) in 1707.

It’s important to keep the work of composers like her—women or otherwise—in perspective. The scores and papers that we have can tell us a lot about her musical practices and ideas, which is always good. She’s also not a typical example of a woman composer or performer at the time, and it’s important to remember that her experience is an exception and not a rule.